Imposter syndrome in social work is one of those experiences that almost everyone has but few people name directly.

Imposter syndrome in social work is one of those experiences that almost everyone has but few people name directly.

You passed your licensing exam.

You got the job.

You’re doing the work.

So why does it still feel like someone is going to realize you don’t actually know what you’re doing?

For many early career social workers, this quiet fear becomes a daily companion. It’s rarely discussed openly in training programs, which makes it easy to assume it means something personal or pathological.

In reality, imposter syndrome in social work is a common and understandable response to the conditions of early social work practice.

Quick Answer: How to Overcome Imposter Syndrome in Social Work

Imposter syndrome in social work is not a confidence problem – it’s a nervous system response to visibility and responsibility. Here’s what actually helps:

4 Evidence-Based Approaches That Work

- Quality Clinical Supervision – Find a supervisor who welcomes “I’m not sure” rather than treating uncertainty as a red flag. This normalizes the learning process.

- Peer Consultation Spaces – Connect with other early-career social workers where uncertainty is normalized, not hidden. You’re not alone in this.

- Balanced Feedback – Seek feedback that acknowledges growth AND areas for development, not purely corrective feedback that amplifies self-doubt.

- Therapy (When Needed) – If imposter feelings persist beyond 2-5 years or spill into chronic anxiety, therapeutic work can help untangle what’s professional learning vs. personal history.

Timeline: For most social workers, imposter syndrome naturally decreases after 2-5 years of practice as clinical judgment solidifies. This is normal, not a personal failing.

“Growth does not require eliminating doubt. It requires learning how to relate to it with clarity and compassion.”

Why Imposter Syndrome in Social Work Is So Common

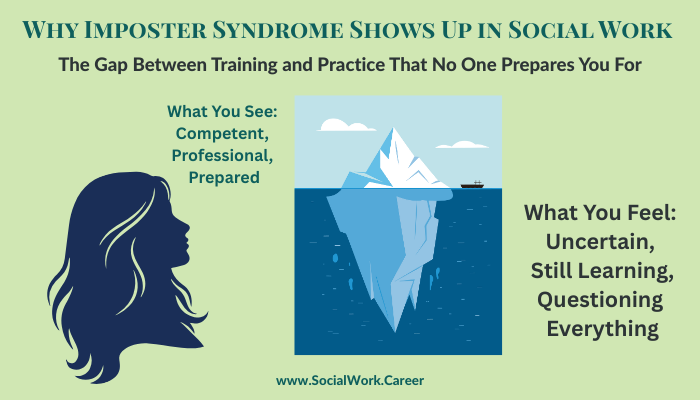

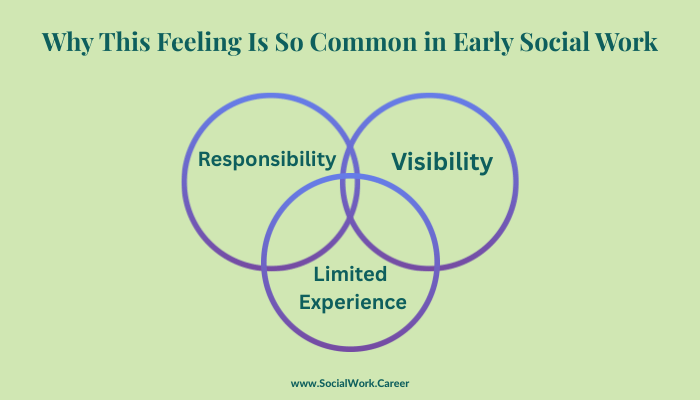

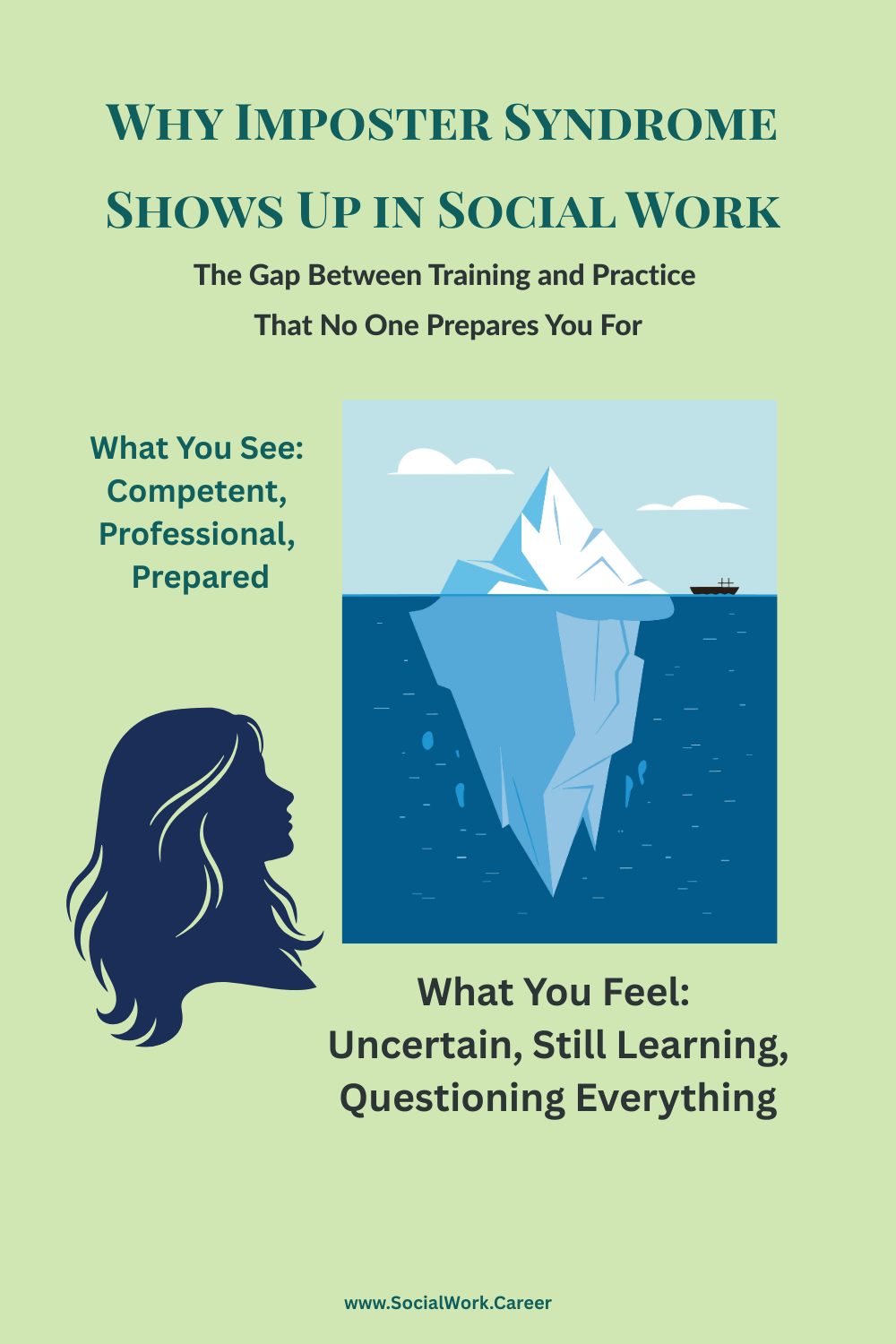

Social work places people in positions of responsibility very quickly. New clinicians are asked to hold complex cases, make ethical decisions, document carefully, and show emotional steadiness often before they feel internally settled.

At the same time, the culture of the field emphasizes reflection, humility, and self examination. These are strengths of the profession. But without context, they can blur into constant self monitoring.

Research supports this experience. A 2023 scoping review of imposter syndrome across health professions found that “imposter syndrome is highly prevalent among healthcare professionals, particularly during training and early career stages” (Panza et al., 2023, p. 967). The study noted that helping professionals face unique vulnerability to imposter syndrome due to the combination of high responsibility, ongoing evaluation, and the relational nature of their work.

Instead of asking: “What am I still learning,” many early career social workers find themselves asking: “Do I belong here at all?”

A Familiar Scenario

A second year MSW sits in a team meeting listening to a colleague confidently outline a case conceptualization.

Internally, the thought is not curiosity.

It is comparison.

“They sound like they actually know what they are doing. I am still Googling trauma models at night.”

Nothing about this moment means the social worker is incompetent.

It reflects how easily learning in public can feel like exposure, a common trigger for imposter syndrome in social work.

How Imposter Syndrome Shows Up at Work

In early career social workers, imposter syndrome often appears quietly.

It can look like staying late to double check documentation, hesitating to speak in supervision, discounting positive feedback, or feeling relief rather than pride when something goes well.

These behaviors are often mistaken for professionalism or diligence. Over time, they can contribute to exhaustion and self doubt rather than growth.

This Is Not a Confidence Problem

Imposter syndrome is rarely about lacking knowledge or skill.

More often, it is a nervous system response to visibility and responsibility. When getting things right once felt essential for approval or safety, the system stays vigilant even after competence increases.

For some social workers, simply understanding this pattern brings relief.

For others, the roots run deeper. Early experiences around performance, criticism, or responsibility can amplify workplace stress in ways that feel disproportionate or hard to turn off.

This is often where therapeutic work can help untangle what is professional learning and what is personal history.

What Actually Helps at a Career Level

Support that reduces imposter syndrome in social work tends to be specific, not generic reassurance.

This includes quality clinical supervision where saying “I am not sure” is welcomed rather than treated as a red flag, peer consultation spaces where uncertainty is normalized, and feedback that is balanced rather than purely corrective.

What helps less is pressure to perform confidence before it has had time to grow. As experienced clinical social workers emphasize, the learning curve in social work practice is real, and normalizing that reality is essential for professional development.

When Additional Support Is Useful

For many social workers, imposter syndrome in social work eases with experience, mentorship, and time.

For others, it becomes persistent and spills beyond work into difficulty resting, chronic anxiety, or harsh self-criticism.

Seeking therapy in these cases does not mean you are unsuited for the profession. It can support nervous system regulation, self trust, and a more sustainable relationship with responsibility.

If you are interested in learning more about how therapy can help with imposter syndrome, especially when it is rooted in deeper patterns, you can explore that further on my therapy site.

A Final Reframe

Feeling like an imposter early in your career does not mean you are behind.

It often means you care deeply and are learning how to trust yourself in a profession that carries real weight.

Growth does not require eliminating doubt. It requires learning how to relate to it with clarity and compassion.

Understanding imposter syndrome in social work as a structural issue rather than a personal failing can help reduce the shame and isolation many capable professionals experience.

FAQs

Is imposter syndrome in social work common?

Yes, imposter syndrome in social work is extremely common, particularly during the first 2-5 years of practice. Research suggests that most helping professionals experience it at some point in their careers, especially when transitioning from academic training to clinical practice.

Why do social workers experience imposter syndrome more than other professions?

Social workers experience high rates of imposter syndrome because the profession combines several risk factors: immediate client responsibility, continuous evaluation through supervision, a culture that emphasizes reflection and humility, and a significant gap between theoretical training and the emotional complexity of real-world practice.

When does imposter syndrome in social work typically improve?

For most social workers, imposter syndrome naturally decreases after 2-5 years of practice as clinical judgment solidifies and self-trust builds. However, improvement depends heavily on the quality of supervision, access to peer support, and workplace culture that normalizes the learning process.

References

Bogo, M., Regehr, C., Power, R., & Regehr, G. (2007). When values collide: Field instructors’ experiences of providing feedback and evaluating competence. The Clinical Supervisor, 26(1-2), 99-117. https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v26n01_08

Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 15(3), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086006

Mullangi, S., & Jagsi, R. (2019). Imposter syndrome: Treat the cause, not the symptom. JAMA, 322(5), 403–404.https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.9788

Osborn, C. J. (2004). Seven salutary effects of mentorship for helping professionals. Guidance & Counseling, 19(2), 107-111.

Panza, S., Karas, D., Regan, M., & Pettitt-Schieber, T. (2023). Imposter syndrome in the health professions: A scoping review. Medical Science Educator, 33(4), 961-972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-023-01819-3

Sakulku, J., & Alexander, J. (2011). The impostor phenomenon. International Journal of Behavioral Science, 6(1), 75-97.

About the author:

Dorlee Michaeli, MBA, LCSW, specializes in EMDR therapy for high-achieving professionals struggling with imposter syndrome. She provides consultation for complex cases involving perfectionism and workplace anxiety. Learn more.

I’m so glad you’ve written about this! I certainly try in my supervision groups and with individual supervisees to provide a space where questions and doubt can be shared without pathology or judgement, and where curiosity is valued over “knowing.” I find curiosity to be such a great antidote for imposter syndrome, and I’m so glad that you’ve documented here all the ways that imposter syndrome can lead to burnout and unnecessary stress, and the role of supervision in combating that. Thank you!

I’m so glad this resonated, Lisa, and I most appreciate how you named curiosity as the antidote. Creating supervision spaces where uncertainty isn’t pathologized makes such a difference, especially early on.

One of the most valuable aspects of my post-graduate psychoanalytic training was exactly this: having a space where concerns and feelings were expected, shared openly, and treated as part of the work, which ultimately supported so much growth.

This is so well articulated. I really appreciate the way you locate imposter feelings in the structure and developmental phase of the work, rather than in individual deficiency. The framing around visibility, responsibility, and constant evaluation feels especially accurate. Thank you for naming this so clearly and compassionately.

Thanks so much, Heather. That distinction matters deeply to me. When we locate imposter feelings in structure, training, and developmental context rather than personal deficiency, it reduces shame and opens the door to clarity and support. I appreciate you naming the visibility and evaluation piece so precisely.

Dorlee,

This is a timeless issue and your post is full of useful context and insights. I wrote an article many years ago with Temple University colleague, Claudia Dewane, where we unpacked what we called “new social worker anxiety syndrome.” It was play off of DSM diagnosis, but the spirit behind the article mirrors much of what you’re talking about here: sometimes we’re feeling like impostors because we don’t know but feel like we should, and some times because we actually don’t know. https://www.socialworker.com/feature-articles/career-jobs/Treating_New_Social_Worker_Anxiety_Syndrome_%28NSWAS%29/

Thanks so much, Jonathan, for sharing this and the NSWAS article you and Claudia wrote. It really adds important context to the conversation.

What stood out to me most is how clearly you named something many early career social workers experience but rarely have language for: that anxiety often comes not from personal inadequacy, but from the mix of real responsibility, visibility, and steep learning curves.

Your distinction between feeling anxious because you do not know yet but feel like you should, and feeling anxious because you truly do not know and have not been adequately supported, feels especially important. Both are common. Neither is a personal failing.

In my clinical and consultation work, I see how easily those external pressures get internalized. Without enough normalization and containment, structural stress starts to feel like personal failure and that is often where imposter feelings take hold.

I really appreciate how you framed this as situational rather than something to diagnose away. Naming it clearly has always been part of the antidote.

This really hit. I remember that early-career feeling of thinking everyone else had it figured out while I was still second-guessing myself behind the scenes. I love how you frame this as a normal response to learning in public, not as a personal failing. The way you talk about imposter syndrome as a nervous system thing (not a confidence issue) feels especially important, and honestly, relieving. This is such a good read for anyone in social work who’s quietly wondering, “Do I actually belong here?”

I really appreciate you naming this, Cheryl.

So many people in social work assume that early self-doubt means they don’t belong, when it’s often a normal nervous system response to responsibility, visibility, and care work all happening at once.

Dorlee, this really lands.

The reframe that imposter syndrome isn’t a “confidence problem,” but a nervous-system response to visibility, responsibility and real stakes is such a needed antidote to the shame or embarrassment so many early-career social workers get trapped in.

From a career-coaching lens, I also appreciate the practical and structural your recommendations are: quality supervision that welcomes “I’m not sure,” peer consultation spaces where uncertainty is normalized, and balanced feedback that includes growth and reframing. Those are career sustainment strategies, not just positive thinking.

One thing I see a lot is how imposter syndrome shows up right when people are advancing in their career such as a new role, licensure, first leadership responsibility, presenting in public, or applying for a stretch job. The story becomes “I’m fooling everyone,” when the truth is often: I’m learning in public. Your point about the first 2–5 years being a normal developmental window is reassuring, especially for folks who interpret anxiety as evidence they don’t belong.

Thank you for naming this so clearly and compassionately, and for grounding it in the realities of practice culture, supervision, and responsibility rather than personal deficiency.

Thanks so much for this, Jennifer. I really appreciate the care and nuance you brought to it.

I’m especially glad you named how imposter experiences often surface at moments of growth (new roles, visibility, responsibility), not as evidence of deficiency, but as part of learning in public. That developmental lens matters so much.

And yes, supervision, consultation, and environments that welcome “I’m not sure” are not soft supports; they’re essential structures for sustainability. When uncertainty is held relationally and structurally, the nervous system doesn’t have to carry it alone.