Financial stress social workers face often gets reduced to one simple explanation: low pay. You chose social work because you wanted to help people. You knew the salary wouldn’t be impressive. You were okay with that trade-off. But somewhere along the way, the financial stress became unbearable. Maybe you’re carrying student loan debt that feels insurmountable on a social worker’s salary. Maybe you’re watching colleagues leave the profession because they can’t afford to stay. Maybe you’re working a second job just to cover basics, which means you have less energy for the clients who need you most. Or maybe, and this is the part nobody talks about, you’re financially stable by most measures, but you still feel financially stressed.

Financial stress social workers face often gets reduced to one simple explanation: low pay. You chose social work because you wanted to help people. You knew the salary wouldn’t be impressive. You were okay with that trade-off. But somewhere along the way, the financial stress became unbearable. Maybe you’re carrying student loan debt that feels insurmountable on a social worker’s salary. Maybe you’re watching colleagues leave the profession because they can’t afford to stay. Maybe you’re working a second job just to cover basics, which means you have less energy for the clients who need you most. Or maybe, and this is the part nobody talks about, you’re financially stable by most measures, but you still feel financially stressed.

You make decent money for social work. You have savings. You’re not in crisis. Yet you feel anxious every time you think about money. You can’t enjoy your paycheck. You avoid looking at your accounts. You feel guilty spending on yourself.

Here’s what most people get wrong about the financial stress social workers experience: It’s not just about the salary. It’s about your relationship with money, and that relationship was formed long before you became a social worker.

Quick Answer: Financial Stress Social Workers Face

Financial stress in social work isn’t primarily about low pay—it’s about your relationship with money. This relationship is shaped by childhood experiences, professional conditioning, and daily exposure to financial trauma. Even financially stable social workers experience money anxiety because the stress lives in your nervous system, not your bank account.

5 Unique Financial Burdens Social Workers Carry

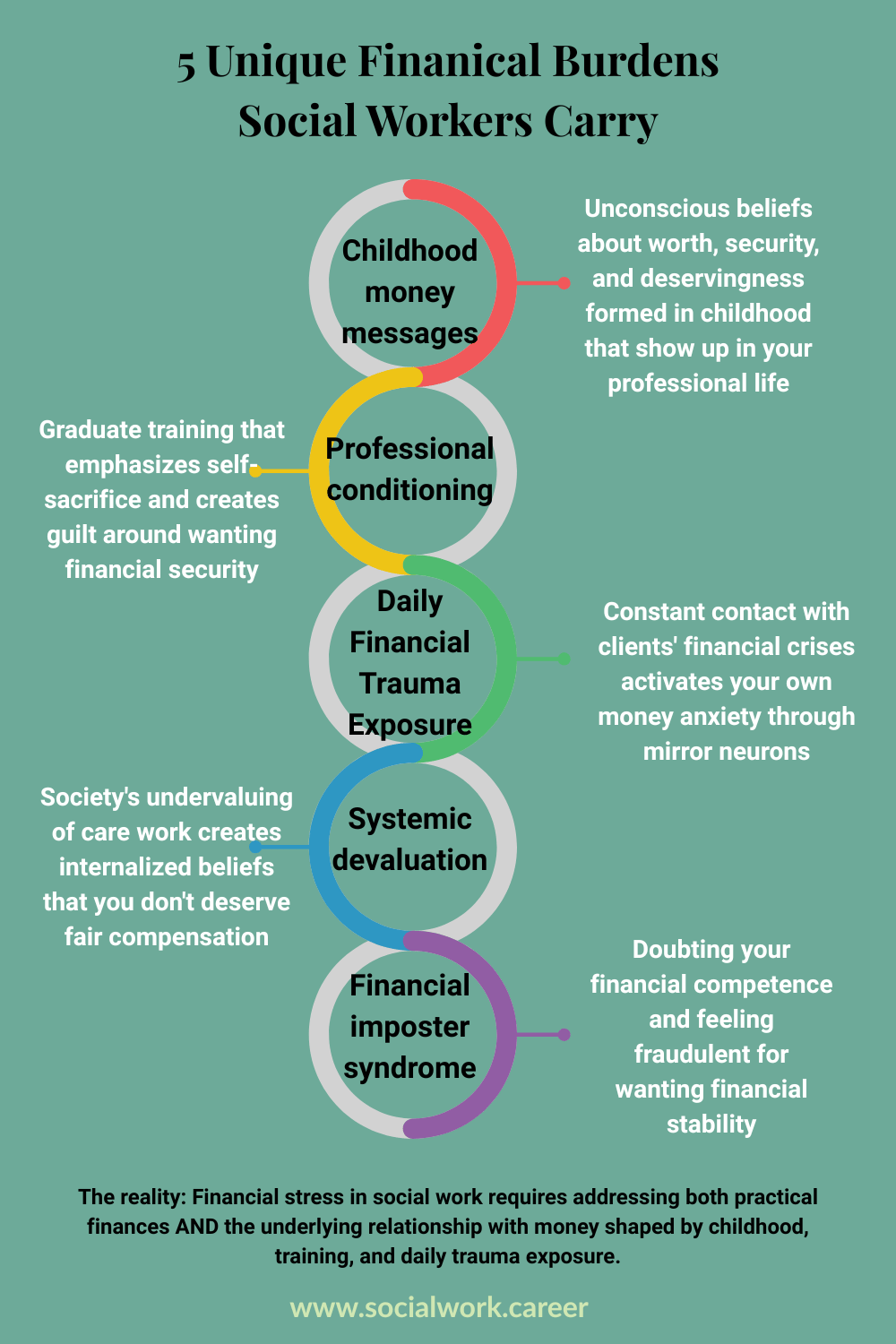

- Childhood Money Messages – Unconscious beliefs about worth, security, and deservingness formed in childhood that show up in your professional life and financial decisions.

- Professional Conditioning – Graduate training and field culture that emphasizes self-sacrifice, reinforces the “helper” identity, and creates guilt around wanting financial security.

- Daily Financial Trauma Exposure – Constant contact with clients’ financial crises activates your own money anxiety and creates vicarious financial trauma through mirror neurons.

- Systemic Devaluation – Society’s undervaluing of care work creates internalized beliefs that you don’t deserve to be well-compensated for emotional labor.

- Financial Imposter Syndrome – Doubting your financial competence, attributing struggles to personal failure rather than systemic issues, and feeling fraudulent for wanting financial stability.

Why Budgeting Advice Doesn’t Fix Financial Anxiety

Traditional financial planning addresses symptoms, not sources. When financial stress is rooted in your nervous system—shaped by childhood experiences, professional conditioning, and daily trauma exposure—a budget spreadsheet won’t resolve the anxiety. You need trauma-informed approaches like EMDR therapy that address the worthiness wounds underneath financial stress: the belief that your worth must be proven through sacrifice, that you don’t deserve ease, or that caring about money makes you selfish.

Research Finding: Approximately 75% of social workers experience burnout, with financial stress as a significant contributing factor. Financial stress isn’t just about money—it’s about professional survival patterns that affect clinical work, boundary-setting, and career sustainability.

Financial stress in social work requires addressing both practical finances AND the underlying relationship with money shaped by childhood, training, and daily trauma exposure.

Quick check: Do any of these sound familiar?

- You avoid checking your bank account even when you know you’re fine

- You feel guilty every time you spend money on yourself

- You can’t accept compliments about your financial decisions

- You downplay your financial stress because “others have it worse”

- You feel anxious about money even when the numbers say you’re okay

If you said yes to 2 or more, keep reading.

The Financial Stress Social Workers Face Goes Beyond Salary

Social workers carry a specific kind of financial burden that goes beyond low pay.

We’re trained to put others first. From day one in social work school, we learn to prioritize client needs, agency needs, community needs. We learn that self-care is important (in theory), but we practice self-sacrifice.

We internalize scarcity. We work with clients in poverty. We see the impact of financial instability every single day. We absorb their financial stress into our own nervous systems. Even when we’re financially stable, we carry the weight of knowing how quickly things can fall apart.

We feel guilty for having more. If you grew up with financial privilege and now work with clients in poverty, you might feel shame about your relative security. If you grew up with financial struggle and now earn more than your family, you might feel guilt about “leaving them behind.”

We’re taught that money is selfish. Social work culture often frames financial ambition as antithetical to our values. Wanting to earn more, negotiate for raises, or build wealth can feel like a betrayal of the profession’s mission.

We absorb our clients’ financial trauma. Hearing stories of eviction, food insecurity, and impossible choices all day doesn’t just affect our clients; it rewires our own nervous systems around money and safety.

These dynamics create the specific financial stress social workers carry, a burden that no amount of budgeting advice will fix.

The Double Burden: Imposter Syndrome Meets Financial Stress

Social workers face a unique intersection of imposter syndrome and financial stress that compounds both conditions.

Research shows that approximately 70% of people experience imposter syndrome at some point in their lives, and social workers are particularly vulnerable.

You entered a helping profession driven by values and purpose, yet you’re confronted daily with:

- Societal messages that devalue care work (“Those who can’t, teach… or do social work”)

- Low compensation that doesn’t match your education, expertise, or emotional labor

- The expectation to martyr yourself financially for your calling

- Guilt about wanting financial stability when your clients are struggling

Let’s Be Clear About the Financial Reality

The salary disparity is real and measurable.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and NASW data:

• The median salary for social workers is approximately $55,000-$62,000, depending on setting

• This requires a master’s degree (MSW) and often clinical licensing (additional training and supervision hours)

• Average MSW student loan debt: $115,000-$150,000

• For comparison: school psychologists (also master’s-level helping professionals) earn a median of $81,500; occupational therapists earn $93,000

That’s a $20,000-$30,000 gap for similar education levels, similar emotional labor, and similar client-facing work. Over a career, that gap compounds to hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost earnings, retirement savings, and financial security.

This structural undervaluation is real, unjust, and needs to change.

AND, even if every social worker got a 30% raise tomorrow, many would still carry the psychological patterns that financial stress created. Because the issue isn’t only about the paycheck.

You doubt your competence with money: “I chose this profession, so I should have known I’d struggle financially. I must be bad with money.”

You attribute financial struggles to personal failure: Rather than recognizing systemic undervaluation of social work, you blame yourself for not budgeting better or working harder.

You feel fraudulent wanting financial security: “Real social workers don’t care about money. If I’m worried about finances, maybe I’m not cut out for this work.”

You can’t internalize your worth: Despite your degrees, licenses, and expertise, you struggle to charge appropriate fees in private practice or advocate for raises.

Why This Matters For Your Practice

The financial stress social workers carry doesn’t just affect personal life; it directly impacts your ability to do your job.

When financial stress social workers experience goes unaddressed, you:

- Have less cognitive capacity for complex clinical work

- Make decisions from a place of scarcity rather than abundance

- Struggle to set boundaries with clients (because you need the work)

- Can’t afford supervision or continuing education that would improve your practice

- Consider leaving the profession not because you don’t love it, but because you can’t afford to stay

- Bring your own financial anxiety into the room with clients

- Model financial stress and scarcity to the very clients you’re trying to help

The irony: Social workers are trained to help people heal their relationships with money and resources. Yet many of us are struggling with our own financial stress, often without even realizing it’s a relationship issue, not just an income issue.

The Hidden Pattern: Your Money Relationship Shapes Your Social Work Practice

Your relationship with money may impact the quality of care you provide.

If you grew up with financial instability, you might:

- Over-identify with clients in poverty (losing professional boundaries)

- Feel unable to charge appropriate fees if you’re in private practice

- Struggle to advocate for your own needs (raises, caseload limits, supervision)

- Experience burnout faster because you’re operating from a place of scarcity

If you grew up with financial privilege, you might:

- Struggle to understand clients’ financial constraints

- Feel guilt about your relative security

- Avoid discussing money with clients (because it feels uncomfortable)

- Underestimate the impact of financial stress on your clients’ mental health

If you experienced financial trauma, you might:

- Absorb clients’ financial stress into your own nervous system

- Struggle to maintain professional boundaries around money

- Feel triggered by discussions of poverty or financial instability

- Carry unprocessed financial anxiety that affects your clinical presence

None of these patterns make you a bad social worker. They make you human. But they do affect your practice, and your wellbeing.

The Perfect Storm

For social workers, childhood experiences and professional training collide to create a perfect storm:

1. Childhood experiences formed unconscious beliefs: “Money isn’t safe,” “I don’t deserve ease,” “Struggle proves commitment”

2. Professional training reinforced self-sacrifice: “Good social workers sacrifice,” “Self-care is selfish,” “Put others first always”

3. Systemic undervaluation confirmed worthlessness: “Care work isn’t worth much,” “You should be grateful for anything,” Society’s message that helping professions don’t deserve compensation

4. Daily trauma exposure activates old wounds: Absorbing clients’ financial stress into your own nervous system, retraumatizing your money anxiety with every session

And here’s the devastating cycle: Financial stress increases imposter feelings, and imposter feelings prevent you from addressing financial stress.

When you feel like a fraud, you:

- Don’t negotiate for raises (you don’t believe you deserve them)

- Undercharge in private practice (you attribute success to luck, not skill)

- Avoid financial planning (you don’t trust your ability to manage money)

- Absorb clients’ financial stress (you don’t have strong enough boundaries)

- Stay in jobs that undervalue you (you don’t believe you’re competent enough for better)

Even When You’re “Doing Okay”

You might be reading this thinking: “But I’m doing okay financially. I’m not in crisis. Why do I still feel so stressed?”

“This isn’t about the numbers. This is about your nervous system. Your rational brain knows you’re okay, but your amygdala is still operating on old programming.”

This is the part that’s hard to talk about in social work circles.

You make decent money for a social worker. You have savings. You’re meeting your bills. By most objective measures, you’re financially stable.

Yet you:

- Feel anxious every time you think about money

- Can’t enjoy your paycheck without guilt

- Avoid looking at your accounts

- Feel shame spending on yourself

- Carry constant low-level financial stress

- Wonder if you can afford to stay in social work long-term

This isn’t about the numbers. This is about your nervous system.

Your rational brain knows you’re doing okay. But your amygdala (threat detection system) is still operating on old programming:

- “Money is never safe”

- “I don’t deserve financial ease”

- “Caring about money makes me selfish”

- “I should be grateful for what I have”

- “Real social workers sacrifice”

And every time you interact with clients in financial crisis, that programming gets reinforced. Your nervous system absorbs their stress. You leave sessions carrying financial anxiety that isn’t even yours.

How Financial Stress Social Workers Experience Leads to Burnout

Research shows that approximately 75% of social workers report experiencing burnout at some point in their careers. Financial stress is a significant contributing factor.

One of the methods to prevent social worker burnout is to employ self-compassion.

The connection is direct:

The financial stress social workers carry means you:

- Can’t afford to take time off (even when you desperately need it)

- Stay in jobs with poor working conditions (because you need the income)

- Don’t have resources for therapy, supervision, or professional development

- Bring financial anxiety into your clinical work

- Feel resentful toward clients (because you’re sacrificing so much)

- Consider leaving the profession

When financial stress is unaddressed:

- Compassion fatigue increases

- Boundaries deteriorate

- Clinical presence suffers Self-care becomes impossible

- Leaving feels inevitable

But here’s what’s crucial to understand: This isn’t primarily a budgeting problem. It’s a professional survival pattern.

The Worthiness Wound

Both financial imposter syndrome and money beliefs are fundamentally about worthiness.

Imposter syndrome says: “I haven’t earned this success. I don’t deserve recognition.”

Financial stress says: “I don’t deserve security. I don’t deserve ease.”

The common denominator? A deep, often unconscious belief that your worth is conditional – that it must be constantly proven through:

- How much you sacrifice

- How little you need

- How hard you work

- How much you give

- How selfless you are

For social workers, this belief gets reinforced at every level:

- Childhood (“Your value depends on what you provide”)

- Education (“Put others first”)

- Training (“Self-care is selfish”)

- Work culture (“Real social workers sacrifice”)

- Client interactions (“You have more, you should feel guilty”)

- Society (“Social work isn’t ‘real’ work”)

No wonder you can’t just “budget better” and feel secure.

Why Traditional Financial Advice Fails (And What Actually Works)

Budgeting apps can’t rewire your nervous system. Trauma-informed approaches target the root: the childhood experiences and professional conditioning that created these patterns. When you process the memories where these beliefs formed—”money isn’t safe,” “I don’t deserve ease,” “wanting more makes me selfish”—your relationship with money shifts at the neurological level, not just the intellectual level.

EMDR therapy is particularly effective for this work, as it processes traumatic memories and updates the beliefs formed in those experiences. Other approaches that target the nervous system and unconscious patterns, such as somatic therapy, Internal Family Systems (IFS), or psychodynamic work, can also be effective. The key is addressing the root patterns, not just the surface symptoms.

This trauma-informed approach aligns with the work pioneered by Reeta Wolfsohn, CMSW, founder of the Center for Financial Social Work, who developed Financial Social Work as an interactive behavioral model that helps people explore and address their unconscious feelings, thoughts, and attitudes about money. By combining trauma-informed therapy with Financial Social Work principles, you can address both the practical and psychological dimensions of financial stress.

If This Resonates

If you’re reading this and thinking “Yes, this is exactly what I experience,” you’re not alone.

The financial stress social workers feel isn’t because you’re bad with money.

It’s not because you’re ungrateful for your salary.

It’s not because you chose the wrong profession.

This isn’t a budgeting problem. It’s a professional survival pattern.

It’s what happens when:

- Childhood beliefs about worth and money

- Professional training in self-sacrifice

- Systemic undervaluation of care work

- Daily exposure to clients’ financial trauma

- Cultural messages about “good” social workers

All collide in your nervous system.

And that nervous system is doing exactly what it was trained to do: prioritize others, minimize your needs, equate worth with sacrifice, and stay hypervigilant about money.

The problem isn’t you. The problem is that no one taught you how to update the programming.

In the next post, I’ll share how early money messages combine with professional training to create this pattern, and more importantly, how Financial Social Work and EMDR therapy can help you build a sustainable career in social work without sacrificing your own wellbeing.

Frequently Asked Questions About Financial Stress Social Workers Face:

Why do social workers experience financial stress even with stable incomes?

Financial stress in social work isn’t just about salary; it’s rooted in your relationship with money. This relationship is shaped by childhood experiences, professional training that emphasizes self-sacrifice, daily exposure to clients’ financial trauma, and internalized beliefs that equate worth with sacrifice. Even financially stable social workers may experience anxiety around money due to these deeply ingrained patterns, not their actual financial situation.

How does financial stress affect social work practice?

Financial stress reduces cognitive capacity for complex clinical work, makes it harder to set boundaries with clients, and can lead to burnout. Social workers may make decisions from scarcity rather than abundance, struggle to charge appropriate fees, absorb clients’ financial anxiety, and consider leaving the profession, not because they don’t love the work, but because financial stress makes it unsustainable.

What causes financial imposter syndrome in social workers?

Financial imposter syndrome occurs when social workers doubt their financial competence, attribute financial struggles to personal failure rather than systemic issues, and feel fraudulent for wanting financial security. It’s reinforced by societal devaluation of care work, cultural messages that “good social workers don’t care about money,” and guilt about having more resources than clients.

How do childhood money messages affect social workers?

Early money messages from caregivers create unconscious beliefs about worth, security, and deservingness that show up in professional life. Social workers who grew up with financial instability may over-identify with clients, struggle to charge appropriate fees, and operate from scarcity. Those from privileged backgrounds may feel guilt that prevents healthy financial boundaries. These patterns affect clinical work, self-advocacy, and career sustainability.

What’s the connection between financial stress and social worker burnout?

Research shows approximately 75% of social workers experience burnout, with financial stress as a significant factor. Financial stress prevents taking needed time off, keeps workers in poor conditions, reduces access to therapy and supervision, brings anxiety into clinical work, and can lead to resentment toward clients. It’s not primarily a budgeting problem; it’s a professional survival pattern that requires addressing both practical finances and the underlying relationship with money.

Can therapy help with financial stress in social work?

Yes. EMDR therapy and trauma-informed approaches can help process the childhood experiences and professional conditioning that created problematic money patterns. Therapy addresses the worthiness wounds underneath financial stress, the belief that worth must be proven through sacrifice, that you don’t deserve ease, or that caring about money makes you selfish. This goes deeper than financial planning, targeting the nervous system patterns that drive financial anxiety.

Is it normal to feel guilty about wanting a higher salary as a social worker?

Yes, this guilt is extremely common and stems from professional conditioning that equates financial ambition with selfishness. Social work culture often frames wanting to earn more as antithetical to the profession’s values. But financial security doesn’t make you less committed to helping others; it actually enables you to stay in the profession longer and show up more fully for clients. The guilt is a symptom of the worthiness wound, not evidence that you’re wrong to want fair compensation.

Ready to address the root of financial stress? Learn how EMDR therapy and Financial Social Work can help you build a sustainable social work career without sacrificing your wellbeing in the next post in this series.

References:

Bravata, D. M., Watts, S. A., Keefer, A. L., Madhusudhan, D. K., Taylor, K. T., Clark, D. M., … & Hagg, H. K. (2020). Prevalence, predictors, and treatment of imposter syndrome: A systematic review. *Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35*(4), 1252-1275.

Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. *Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 15*(3), 241-247.

Lloyd, C., King, R., & Chenoweth, L. (2002). Social work, stress and burnout: A review. *Journal of Mental Health, 11*(3), 255-265.

Ravalier, J. M., McVicar, A., & Munn-Giddings, C. (2024). Relationships between stress, burnout, mental health and well-being in social workers. *The British Journal of Social Work, 54*(2), 668-690.

Sherraden, M. S., & Huang, J. (2019). Financial social work. In Encyclopedia of Social Work. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.923

Stanley, S., & Sebastine, A. J. (2023). Work-life balance, social support, and burnout: A quantitative study of social workers. *The British Journal of Social Work, 53*(8), 4586-4602.

Wolfsohn, R., & Michaeli, D. (2014). Financial social work. Encyclopedia of Social Work. National Association of Social Workers and Oxford University Press.

About the author:

Dorlee Michaeli, MBA, LCSW, specializes in EMDR therapy for high-achieving professionals struggling with imposter syndrome. She provides consultation for complex cases involving perfectionism and workplace anxiety. Learn more.

Leave a Reply